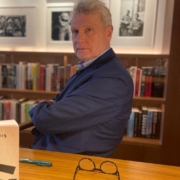

Tom Lanoye

Tom Lanoye (b.1958) is known as a novelist, theatre

author, poet, scriptwriter and performer. His publications

include bestsellers such as Cardboard Boxes,

At War and Fortunate Slaves. In 2012, he wrote the

Book Week Gift Clear Sky. In 2014, he was awarded

the Constantijn Huygens Prize for his oeuvre.

Pied-à-Terre

How many Belgians would dream of a pied-à-terre in Amsterdam? To be honest: very few. Most Belgians dream of Paris, they swear by Berlin, they laud London for its shops and Barcelona for its Ramblas. The snobs generally get moist for Venice. And what Belgian wasn’t born to be a snob and stay a snob — beneath a layer of politeness known as slyness?

Take me, for instance. I laugh at all the Belgians I note above, and I amaze them by stating that there is no better place in Europe than Amsterdam to eat and wander and squander, and visit museums and party and visit theatre and sleep. Certainly in Corona times, because all the other tourists have finally kept away in droves, so all those ridiculous cheese ball and Nutella chocolate paste shops will hopefully go bankrupt. I’ve never said that Amsterdam is perfect.

From another perspective, my mother-in-law was born here, my publisher is housed in the finest building on the Herengracht, and my Amsterdam pied-à-terre is also on that splendid canal. I feel at home there without having to rob a couple of banks first. Because the house prices will never improve again, not anywhere above the Moerdijk down south. I’ve never said that the whole of the Netherlands is perfect. What I have said lately — watching the non-forming government in The Hague — is that the Netherlands is transforming into Belgium at a rapid speed. So, as a Belgian, you should certainly make tracks for Amsterdam as fast as possible, before it’s transformed into Antwerp or Brussels. Believe me, they are both even further from perfect.

If they do travel to Amsterdam, these curious Belgians, then I hope they’ll pass by my pied-à-terre. For years, I’ve felt so at home in the Hotel Ambassade that I sometimes want to call the police to have the other guests expelled for violation of domestic privacy. The phrase sounds even better in Flemish: Woonstschennis, or home invasion.

You never used to see Dutch authors in the Hotel Ambassade. Perhaps that’s where the name comes from. You had to be a foreigner to be let in. Then, Arnon Grunberg started writing. And so, travelling too. People used to travel to learn; since Grunberg, you travel to write. He’s not always perfect either, but he does have taste. Otherwise, he’d have chosen another hotel as a pied-à-terre in the city of his birth. At the moment, he’s here more than I am.

Sometimes, I see him at breakfast and then we wave at each other. I’ll admit, that’s the advantage of a hotel versus a real pied-à-terre. In a real pied-à-terre, you seldom find yourself waving at Arnon Grunberg over breakfast. I have, in the past, waved at Sandro Veronesi and Donna Tartt, but they didn’t wave back. That’s how it is with foreigners. They look away from other foreigners.

A real pied-à-terre should have a family. With the Ambassade, this is a sort of African extended family. I truly don’t know any other hotel in the world — yes, I confess: I do sometimes travel to other cities — where I’m greeted so warmly by people who know my name and whose names I know too. During my first post-Corona stay, this was one of the highlights, no irony. The Slavery exhibition in the Rijksmuseum and the guided tour of the Hermitage were great, of course, but I equally enjoyed having a nice chat with Claudia and Wim and Eelco and Tamara e tutti quanti. With us complaining that we’d had to miss each other for two years. And counting on our fingers how many years it must have been since me and my guy first spent the night here.

That was on the occasion of a Book Ball during a Book Week, when they were spotlighting Flemish letters. So, a very long time ago. Hugo Claus and Harry Mulisch were still alive. They were standing next to each other in the beautiful lobby of the Stadsschouwburg Theatre, like a regal couple who were offering audiences and hands to kiss to the plebs. We, the plebs, preferred to go off and dance and drink on the stage in the theatre auditorium.

That night, my man couldn’t find one of his contact lenses in the bathroom of our future pied-à-terre. Although he’d only just taken them out, both of them. In my recollection, we crawled around on our knees for an hour, searching and swearing, until we finally turned in.

We did find the lens again, just before breakfast. In a crack between the washbasin and the wall. You won’t hear me say that my pied-à-terre is perfect. For a writers’ hotel, there are an awful lot of paintings around. But the library is even bigger. And, apart from one crack, I’ve had few other complaints in all these years.

View the column on the website of ‘Het Parool’.

What is a writers’ hotel without writers? A pen without ink? For a period of six months in 2021, one author a week was invited to stay at the Ambassade Hotel and describe their writing lives at that time. Throughout the period May to November 2021, the newspaper Het Parool published the Writers’ Hotel columns in its weekly Arts Section.

Read more about this column project in collaboration with ‘Het Parool’.

Would you like to stay at the writers’ hotel as well? Enjoy a unique experience in the Ambassade Hotel with these special offer packages or come and admire the library after visiting our sunny terrace on the Herengracht!